Case of the week #631

(1) Radiologist, Imagerie Capricorne, Prenatal Diagnosis Center; (2) Obstetrician, CHU La Reunion, Prenatal Diagnosis Center; (3) Pediatric Nephrologist, CHU La Reunion, Prenatal Diagnosis Center; (4) Resident, Mayotte Hospital; (5) Sonographer, Mayotte Private Sector; Reunion Island; (6) Centro Médico Recoletas, Valladolid, Spain

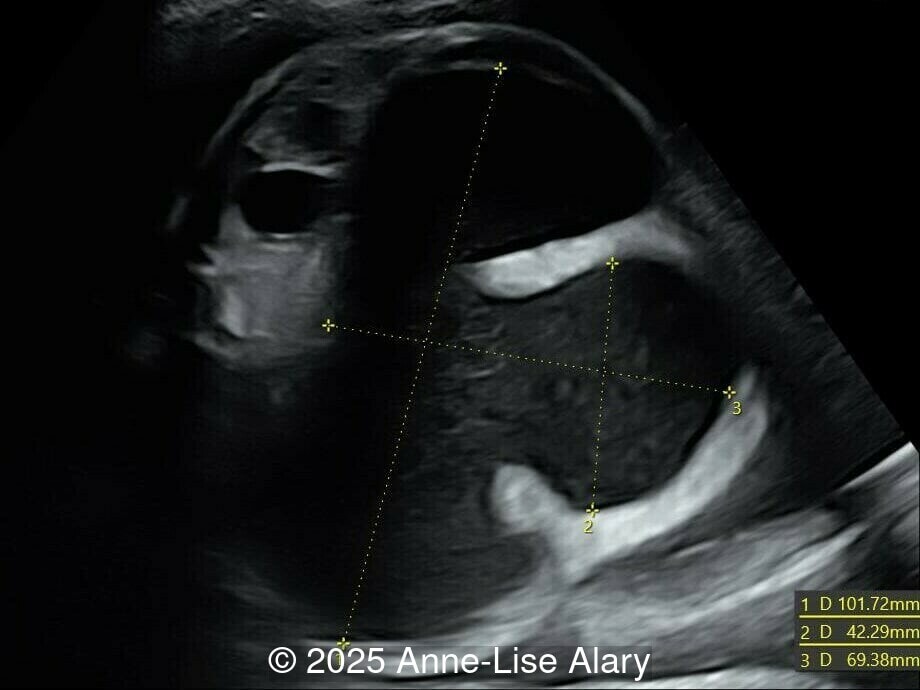

20-year-old primigravid woman, presented late for prenatal care at 29 weeks gestation. There was no consanguinity, and no pertinent past medical or familial history. We found the following anomalies:

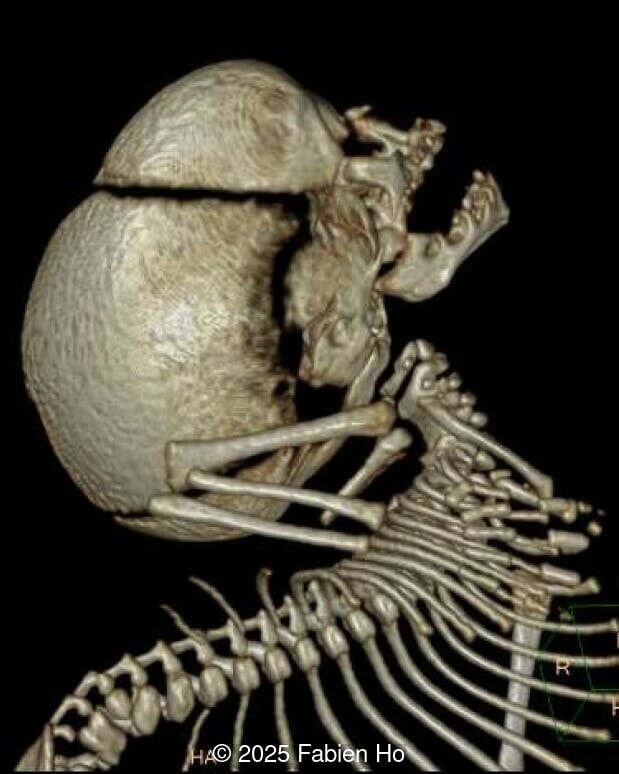

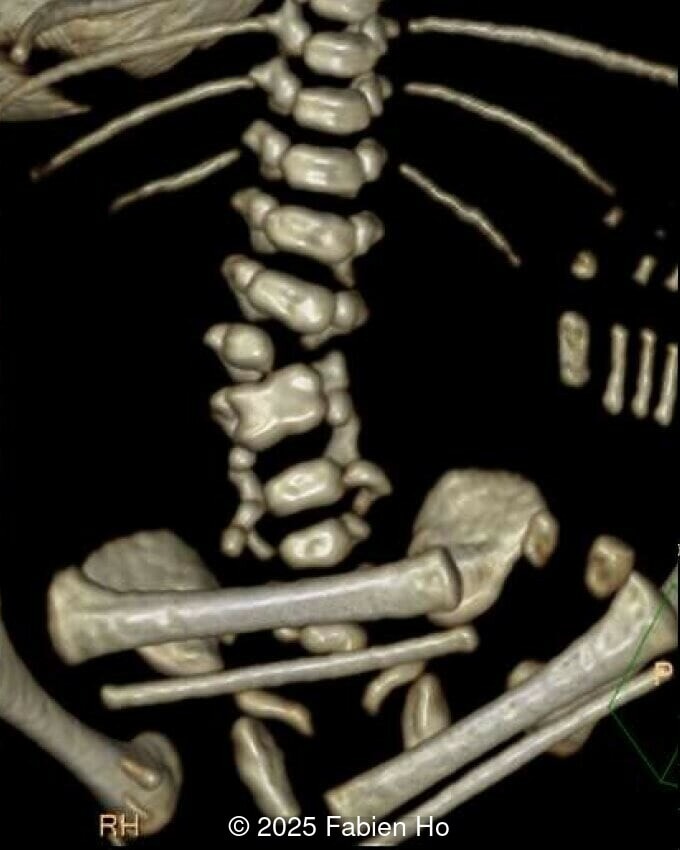

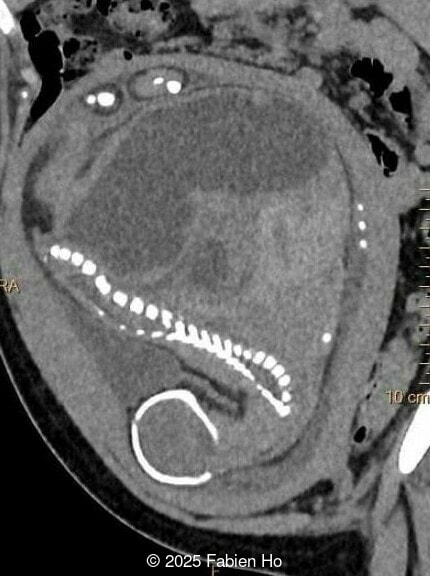

At 36 weeks gestation, the abdominal findings were unchanged however, the bones appeared short (<1st percentile) and the spine had an unusual appearance, therefore a computed tomography was performed at 37 weeks gestation.

What is your diagnosis ?

View the Answer Hide the Answer

Answer

We present a case of Prune Belly Syndrome

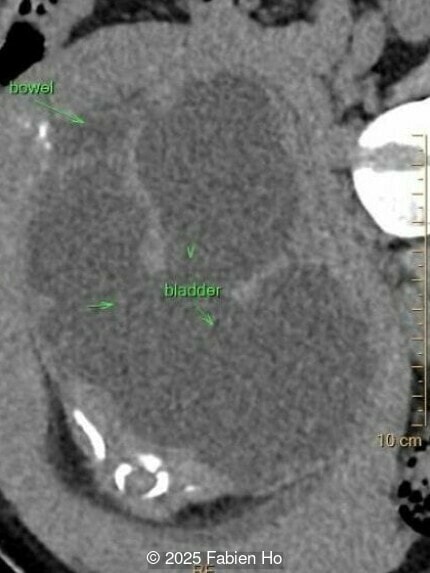

Our prenatal ultrasound revealed a male fetus with megabladder, dilation of both ureter and kidneys, and thinned kidney parenchyma consistent with Lower Urinary Tract Obstruction (LUTO). Additional findings suspected on ultrasound and confirmed on computed tomography included:

- Short long bones (<1st percentile), normal mineralization, and no sign of lethal chondrodysplasia

- Evidence of Potter's sequence due to the lower urinary tract obstruction with small thorax compared to the abdomen, hyperextended neck, and pes varus.

- Dysostosis: Hemivertebrae L3, fused L4-L5, abnormal left foot with short metatarsals and missing phalanges

- Suspicion of dilated bowel in the left flank, in addition to dilated urinary tract

The findings of lower urinary tract obstruction, male phenotype, vertebral dysostosis, limb anomaly, and suspected bowel dilation led us to the following differential diagnosis:

- Prune-Belly syndrome

- VACTERL association

- MMHIS (megabladder microcolon hypoperistalsis), though usually described in females

The couple chose to deliver naturally. After prenatal needle aspiration of the bladder, the baby was delivered at 39 weeks gestation. Postnatal findings were consistent with Prune-Belly Syndrome with flaccid abdominal wall (similar to prune skin), lower urinary tract obstruction in a male fetus, imperforate anus requiring colostomy, lumbar hemivertebrae, and left foot hypoplasia including metatarsals and phalanges.

Discussion

Prune-belly syndrome (PBS) is a congenital disorder defined by a characteristic clinical triad that includes abdominal muscle deficiency, severe urinary tract abnormalities, and bilateral cryptorchidism in males [1,2]. Initially reported by Fröhlich in 1839 [3], the term ‘‘prune belly syndrome’’ was later coined by Osler in 1901 [4] to reflect the characteristic wrinkled appearance of the abdominal wall in the newborn due to the absence of abdominal wall muscles. Eagle and Barrett reported nine cases in 1950, describing the condition as “Eagle-Barrett syndrome” [5]. It is also known as “triad syndrome”, “abdominal musculature deficiency syndrome”, and “Obrinsky syndrome”. Its reported incidence is between 2 and 4 cases per 100,000 births [6,7], occurring primarily in males although there are rare case reports of this disorder in females [8]. It is also more common in monozygotic and dizygotic twin pregnancies than in singleton pregnancies [9-11].

Two main theories have been proposed as the mechanism of prune-belly syndrome. One suggests that early urethral obstruction causes distention of the bladder, preventing formation of the anterior abdominal wall muscles and descent of the testes [12]. This theory neither explains the condition when the urethra is patent, nor does it explain the lack of development of the PBS phenotype in cases of posterior urethral valves. Other investigators have suggested that the underlying mechanism in prune-belly syndrome is a primary defect in the intermediate and lateral plate mesoderm, which would affect embryogenesis of the abdominal wall musculature, the mesonephric and paramesonephric ducts, and the urinary organs [13]. The ultimate cause of this mesenchymal defect is not well established, and mutations in various genes (HFN1B, FLNA, CHRM3, MYOCD, etc.) have been suggested [1]. A third theory holds that the abdominal laxity in prune-belly syndrome is a simple deformation secondary to abdominal stretching and distention during fetal development [14,15].

Prune-belly syndrome is a multisystem disease. In addition to deficient abdominal wall musculature and bilateral undescended testicles, the typical urologic findings of PBS are distended bladder, hydronephrosis, and renal dysplasia. In some fetuses, urinary obstruction can lead to oligo/anhydramnios and subsequently, to Potter sequence with dysmorphic facies, pulmonary hypoplasia, arthrogryposis, and clubfoot [9]. A registry of birth defects conducted in New York State between 1983 to 1989 found that 70% of the infants with prune belly had defects other than the typical triad sequence, with involvement of the gastrointestinal (24%), musculoskeletal (23%), and cardiovascular (25%) systems [6,9]. The most commonly described gastrointestinal malformations are malrotation of the gut, intestinal obstructions, imperforate anus, ascites, and persistence of the cloaca [16]. Associated musculoskeletal anomalies include clubfeet, limb deficiencies, hip dysplasia, and vertebral malformations [17]. Cardiac defects associated with prune belly syndrome include tetralogy of Fallot, atrial and ventricular septal defects [18]. Additionally, congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation has been identified in fetuses with prune-belly syndrome [19].

The diagnosis of PBS is often made in the second trimester of pregnancy, although it has been described as early as 11 weeks of gestation [20]. The most frequent ultrasound findings are a large, thin-walled bladder accompanied by bilateral hydroureter/hydronephrosis, dysplastic kidneys with echogenic renal parenchyma and renal cortical cysts, and abdominal wall laxity which is better viewed after bladder decompression [21]. Cryptorchidism can be detected prenatally by 28 to 30 weeks gestation when the testes descend into scrotum. There may be a patent urachus, visible as a cystic connection between bladder and umbilicus. Oligohydramnios is a frequent finding, which makes it difficult to visualize the associated anomalies.

Prune belly syndrome can be classified into three prognostic groups depending on severity of renal damage, oligohydramnios, and pulmonary hypoplasia [22]. In group 1, which includes 20% of cases, significant renal dysplasia and pulmonary hypoplasia is present and most patients are stillborn or die shortly after birth. Infants in group 2, representing 40% of cases, have adequate renal function at birth, but may become compromised by obstruction and infection. Patients in group 3, which includes the remaining 40% of cases, have mild urinary tract abnormalities and most survive.

The differential diagnosis in fetuses with dilatation of the bladder, ureters, or both includes megacystis-microcolon-hypoperistalsis syndrome, prune belly syndrome, posterior urethral valves, and urethral atresia [23]. Megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome, an autosomal recessive disorder more common in females, is a rare cause of congenital intestinal and urinary dysfunction that causes massive distention of urinary bladder with hydroureteronephrosis and normal amniotic fluid volume. Posterior urethral valves occur more commonly in male fetuses with findings similar to those found in PBS, however, the distinguishing feature is a thick and trabeculated wall of the dilated bladder that shows a keyhole sign in its lower part due to the dilation of the posterior urethra. Additionally, hydronephrosis and hydroureter are not always present.

In cases of lower urinary tract obstruction, prenatal treatment is a vesicoamniotic shunt, which alleviates the urinary distention and oligohydramnios, interrupting the sequence of renal dysplasia and pulmonary hypoplasia [24,25]. Serial vesicocenteses determine renal function based on urinary electrolytes and are used to select fetal candidates for shunt procedures. Despite this, the rates of fetal termination after early detection of prune belly syndrome are as high as 31% [26]. Approximately one-third of surviving infants suffer from chronic kidney failure requiring peritoneal dialysis and/or kidney transplantation [27].

Refer

[1] Wallner M, Kramar, R. Prune-belly syndrome. In: UpToDate, Kremen J (Ed), Waltham, MA. (Accessed on May 26, 2025.). ences

[2] Brewer FR, Harper LM. Prune-Belly Syndrome. In: Copel JA, ed. Obstetric Imaging. Fetal Diagnosis and Care, 2nd ed. Elsevier, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2018; pages 574-576.e1.

[3] Fröhlich F. Der Mangel der Muskeln, Insbesondere der Seitenbauchmuskeln. [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Würzburg, Germany, 1839.

[4] Osler W. Congenital absence of the abdominal muscle, with distended and hypertrophied urinary bladder. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp.1901; 12:331–333

[5] Eagle JF Jr, Barrett GS. Congenital deficiency of abdominal musculature with associated genitourinary abnormalities: A syndrome. Report of 9 cases. Pediatrics. 1950 Nov; 6(5):721-736.

[6] Routh JC, Huang L, Retik AB, Nelson CP. Contemporary epidemiology and characterization of newborn males with prune belly syndrome. Urology. 2010 Jul; 76(1):44-48.

[7] Pakkasjärvi N, Syvänen J, Tauriainen A, et al. Prune belly syndrome in Finland - A population-based study on current epidemiology and hospital admissions. J Pediatr Urol. 2021 Oct; 17(5): 702.e1-702.e6.

[8] Rabinowitz R, Schillinger JF. Prune belly syndrome in the female subject. J Urol. 1977 Sep; 118(3):454-456.

[9] Druschel CM. A descriptive study of prune belly in New York State, 1983 to 1989. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1995 Jan; 149(1):70-76.

[10] Balaji KC, Patil A, Townes PL, et al. Concordant prune belly syndrome in monozygotic twins. Urology. 2000 Jun 1; 55(6):949.

[11] Patel RV, Marshall D, Millar D, O'connor M. Prune belly sequence in a non-identical twin. BMJ Case Rep. 2014 Jun 25; 2014: bcr2014204371.

[12] Moerman P, Fryns JP, Goddeeris P, Lauweryns JM. Pathogenesis of the prune-belly syndrome: a functional urethral obstruction caused by prostatic hypoplasia. Pediatrics. 1984 Apr; 73(4):470-475.

[13] Stephens FD, Gupta D. Pathogenesis of the prune belly syndrome. J Urol. 1994 Dec; 152(6 Pt 2):2328-2331.

[14] Nakayama DK, Harrison MR, Chinn DH, de Lorimier AA. The pathogenesis of prune belly. Am J Dis Child. 1984 Sep; 138(9):834-836.

[15] Wijesinghe US, Muthucumaru M, Beasley SW. Further evidence of the etiology of prune belly syndrome provided by a transient massive intraabdominal cyst in a female. J Pediatr Surg. 2016 Aug; 51(8):1390-1393.

[16] Wright JR Jr, Barth RF, Neff JC, et al. Gastrointestinal malformations associated with prune belly syndrome: three cases and a review of the literature. Pediatr Pathol. 1986; 5(3-4):421-448.

[17] Loder RT, Guiboux JP, Bloom DA, Hensinger RN. Musculoskeletal aspects of prune-belly syndrome. Description and pathogenesis. Am J Dis Child. 1992 Oct; 146(10):1224-1229.

[18] Yoshida M, Matsumura M, Shintaku Y, et al. Prenatally diagnosed female prune belly syndrome associated with tetralogy of Fallot. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1995; 39(2):141-144.

[19] Kuruvilla AC, Kesler KR, Williams JW, McGee MJ. Congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation of the lung associated with prune belly syndrome. J Pediatr Surg. 1987 Apr; 22(4):370-371.

[20] Yamamoto H, Nishikawa S, Hayashi T, et al. Antenatal diagnosis of prune belly syndrome at 11 weeks of gestation. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2001 Feb; 27(1):37-40.

[21] Jha, P and Woodward PJ. Prune-Belly Syndrome. In: Woodward PJ, Kennedy A, Sohaey R, ed. Diagnostic Imaging Obstetrics, 4th ed. Elsevier, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2021; pages 646-649.

[22] Woodard JR. The prune belly syndrome. Urol Clin North Am. 1978 Feb; 5(1):75-93.

[23] Osborne NG, Bonilla-Musoles F, Machado LE, et al. Fetal megacystis: differential diagnosis. J Ultrasound Med. 2011 Jun; 30(6):833-841.

[24] Perez-Brayfield MR, Gatti J, Berkman S, et al. In utero intervention in a patient with prune-belly syndrome and severe urethral hypoplasia. Urology. 2001 Jun; 57(6):1178.

[25] White JT, Sheth KR, Bilgutay AN, et al. Vesicoamniotic Shunting Improves Outcomes in a Subset of Prune Belly Syndrome Patients at a Single Tertiary Center. Front Pediatr. 2018 Jul 3; 6:180.

[26] Cromie WJ, Lee K, Houde K, Holmes L. Implications of prenatal ultrasound screening in the incidence of major genitourinary malformations. J Urol. 2001 May; 165(5):1677-1680.

[27] Woods AG, Brandon DH. Prune belly syndrome. A focused physical assessment. Adv Neonatal Care. 2007 Jun; 7(3):132-143.

Discussion Board

Winners

Javier Cortejoso Spain Physician

Andres Arencibia United States Physician

Mayank Chowdhury India Physician

CHEN YANG China Physician

Amparo Gimeno Spain Physician

Annette Reuss Germany Physician

Hayley Jacobson Israel Physician

philip pattyn Belgium Physician

Petra Barboríková Slovakia Physician

Joanne Maloney United States Sonographer

Manuel Rodriguez Mexico Physician

Surekha Bhimangouda India Physician

KIM SOCHETRA Cambodia Physician